Moscow reveals cables sent to USSR by British double agent

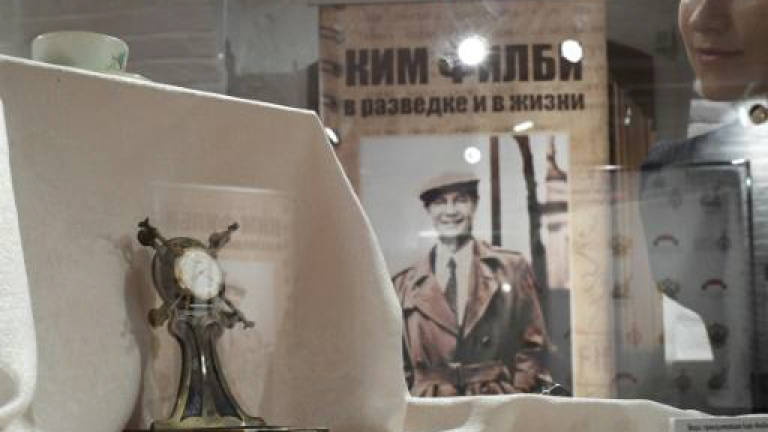

MOSCOW: A new exhibition in Moscow has made public for the first time secret documents that British double agent Kim Philby sent to his Soviet handlers.

Considered one of the KGB's most productive Western recruits – and Britain's biggest Cold War traitor – Philby passed information to Moscow from the 1930s until he was discovered and fled to the Soviet Union in 1963. He died in 1988 at the age of 76.

Philby is still celebrated as a hero by the KGB's successor agency, the FSB, and Russia's foreign intelligence service, the SVR.

SVR director Sergei Naryshkin opened the exhibition "Kim Philby in espionage and in life" at the Russian Historical Society last month. It will run until Oct 5.

"Philby was able to do a lot to change the course of history, to do good and bring about justice. He was a great citizen of the world," Naryshkin said at the opening, where guests included KGB veterans mentored by Philby.

Philby was one of the legendary "Cambridge Five" spy ring of upper class men embedded in the British establishment who were recruited to spy for the Soviet Union during their time at the University of Cambridge in the 1930s.

Most of the documents displayed in the exhibition are from the 1940s and come from the archives of the SVR.

The British cables are marked "top secret" in red. Some of them have been translated into Russian, with one addressed personally to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and his foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov.

One of the documents is a 1944 cable intercepted by Philby from the Japanese ambassador in Italy back to Tokyo about a meeting with fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. Another reveals information on British and American operations in Albania in 1949.

'Patriot of both his homelands'

"Thanks to Philby, all of these reached Stalin's desk," said Konstantin Mogilevsky, head of the Kremlin-backed History of Fatherland Foundation, which helped organise the exhibition.

"Philby was a patriot of both his homelands: Britain and the Soviet Union," said Mogilevsky, claiming "he never put the lives of his British colleagues in danger".

Mogilevsky compared Philby to Edward Snowden, who leaked details of US surveillance programmes and was later granted asylum in Russia.

"What Snowden did was not for money or to make his life better – quite the opposite, he made it a lot worse. In that sense they are similar," he said.

"Russia has always valued those kind of motives," he added.

The exhibition also includes Philby's account of fleeing Beirut on January 23, 1963, after a KGB handler warned him he had been uncovered.

After telling his wife at that time, Eleanor, he would meet her at a restaurant for dinner, he escaped on a cargo ship headed for Odessa in Ukraine.

Philby's 85-year-old Russian widow Rufina Pukhova-Philby, who met him after his defection, attended the opening.

She contributed cigars Cuban leader Fidel Castro gave to Philby and an armchair formerly owned by Guy Burgess, another member of the Cambridge Five who defected to Moscow and died in 1963.

Cold War nostalgia

The exhibition opened ahead of Russian state-controlled Channel One television airing a three-part documentary series based on Philby's career and love life later this autumn.

The Russian intelligence community has a sense of nostalgia for their Soviet heyday, said Sergei Grigoryants, a rights activist who studies Russia's secret services.

"There is a huge longing for those years," he said.

"They are upset that Russia's current spies are people who are in it for money or as a result of blackmail – not for ideological motives like in the 1930s."

But for the Cambridge Five, the reality in Moscow proved far from the socialist dream they imagined back in Britain.

The exhibition makes no mention of Philby's struggle to adapt to life in the USSR, where he was kept under surveillance and never fully mastered the language.

"He didn't understand the world around him," Grigoryants said.

Nevertheless, Philby remained an avowed Communist until his death.

The exhibition displays his address in 1977 to KGB officers on the 100th birthday of KGB founder Felix Dzerzhinsky.

"May we all live to see the red flag hanging over Buckingham Palace!" Philby said. — AFP