THERE is art in leftovers from the kitchen. For instance, turmeric leaves a bright yellow hue, while the leaves of a carrot plant produces a light greenish-brown shade.

Given a chance, Umi Junid, an advocate of producing art from waste, will reel off a list of possibilities that an artist can achieve with onion and potato peel, ginger and every other ingredient for a delicious dish. The fact that such items are also environmentally friendly is a bonus.

Not surprisingly, it was a tribal community that first showed Umi how Mother Nature can be a palette for artists.

The former lecturer in graphic design was sent to Sierra Leone in West Africa eight years ago to guide teachers there.

During visits to a local market, Umi discovered “gara”, the African version of batik. But instead of

using wax, the Africans used plants for dye.

Different colours can be obtained from different species of plants, she told theSun.

In Sierra Leone, the most popular colours are blue derived from the indigo plant and brown produced by kola nuts.

“The patterns are mostly geometric and symmetrical but I was taken in by the beauty of their designs,” she said.

“Every tribe has its own motif.”

Umi realised that the total dependence on natural resources for artistic pursuits could also be applied to Malaysian batik.

However, her knowledge of batik printing was limited.

“All I knew then was that the motifs for batik were usually flora and fauna, and wax was used in the production process,” Umi said.

She was also acutely aware that wax was not environmentally friendly.

To get a better understanding of how batik printing can be done using only natural colours, she travelled to Semarang and Pekalongan, two cities in Central Java, Indonesia.

“I spent two weeks in Semarang with a family to learn how they used the indigo plant to make natural dyes, with the rich blue hue,”

she said.

The entire process, from cultivating the indigo plant to producing the dye, was a family undertaking.

In Pekalongan, the centre of Indonesia’s batik industry, she learnt how to print using natural colours. It would take her another two years for her to perfect her skills, but it paid off.

When she enrolled at Norwich University for her masters in textile design, she started making customised batik coasters with her own motifs that she managed to sell at £7 (RM40) each. Apart from that, she also produced shawls and scarves that she sold online.

But the Covid-19 pandemic changed everything. During the first movement control order in March last year, Umi read an article about how families stocked up additional food to see themselves through the lockdown, only to see some of it ending up in the bin.

“I realised that we end up wasting a lot of ingredients while cooking. Rather than throw them away, I began collecting the leftovers, such as onion and potato peel, garlic and ginger as well as chicken soup,” she said.

That soon started Umi on what she now refers to as her “kitchen waste dye project”.

“With different techniques, I managed to create a multitude of colours.”

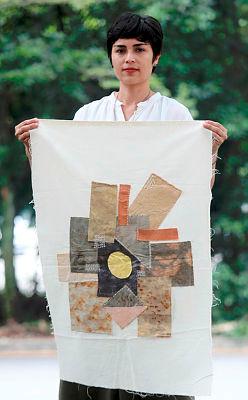

Her kitchen waste dyes now splash across various materials that she promotes on her website DuniaMotif.

Umi’s podcasts have attracted the attention of more than 1,000 subscribers and online magazines from Germany to Japan. And she is not finished yet.

A new project – a self-sustaining dye farm – is on the way.