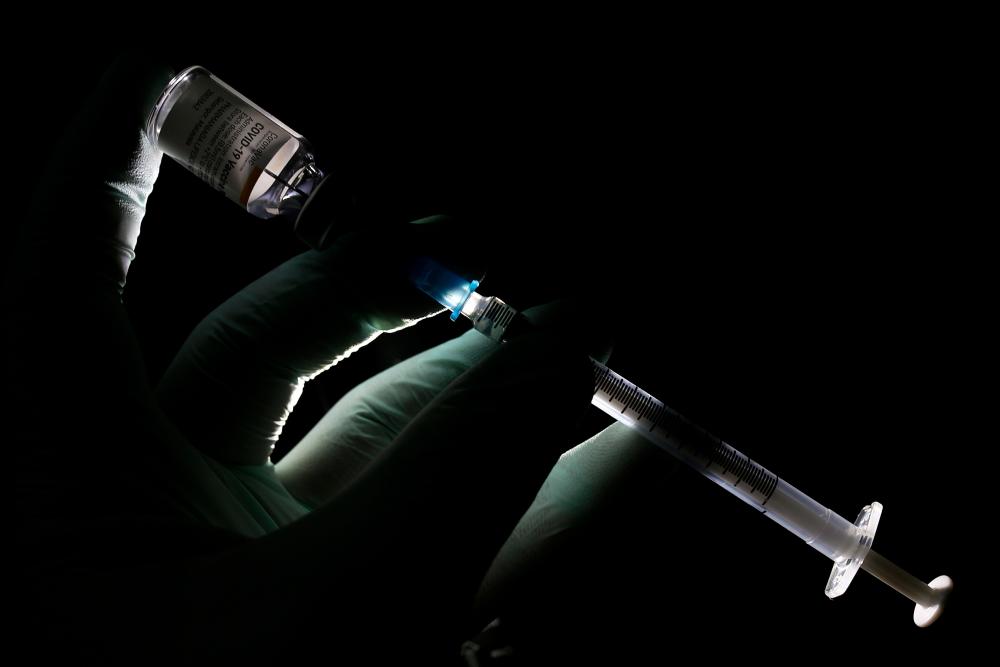

MALAYSIA currently boasts one of the highest vaccination rates in the world, with almost 70% of its adult population fully vaccinated.

It has also started administering vaccines to school students. While this comes as a timely move by the government, vaccine hesitancy among parents and students alike continues to be a huge challenge for healthcare professionals, who believe that any vaccine is better than no vaccine at all.

According to the World Health Organisation vaccine hesitancy can be defined as the delaying or refusal of vaccine despite the availability of adequate vaccines; it is complex.

Conflict of interest

What seems apparent is the tension between individual rights and state interest in the preservation of people’s welfare.

It is understandable that most governments would want their population to be vaccinated as the current Delta variant is ripping through non pharmaceutical preventive intervention that is pushing the herd immunity almost out of reach.

Last month, the Infectious Diseases Society of America estimated the threshold for herd immunity to be 90% of the population instead of the previous 60% to 70%, due to the Delta strain.

Once infected with the Delta strain, even fully vaccinated people can go on to transmit the virus as easily as those who are not vaccinated.

It is no surprise that there have been growing calls by various parties urging the government to vaccinate teenagers under 18. Many have also appealed for the government to

make it mandatory to vaccinate school-going children before classes resume in October.

While there may be hesitancy in regard to vaccinating the young, medical experts globally have long supported children getting a vaccine, although there is concern of children developing myocarditis and pericarditis following the administration of mRNA vaccines.

Although some 2,259 children, who were part of a vaccine study in Europe, did not display any severe side effects including that of myocarditis and pericarditis, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) does not completely state that vaccines would have zero to no side effects in children. On a good note, EMA has since approved the use of the Pfizer (aged 12-15) and Moderna (aged 12-17) vaccine to children.

Studies have consistently proven that the long-term benefits of the vaccine outweighs its side effects. Developed European countries have moved on with the majority of its adult population inoculated and children getting vaccinated. Cuba, known for their medical revolution, has taken a step further by administering vaccines to toddlers.

The Malaysian government was initially hesitant on vaccinating children below the age of 18, due to the possibilities of children developing cardiovascular disease and experiencing severe side effects. But it has now approved administering vaccines to those below the age of 18.

Lesser restrictive measures

Proponents of mandatory vaccination normally justify the importance of getting inoculated based on the grounds of protecting the welfare of others. They often argue that it is necessary to curtail the rights of others, especially in regard to achieving herd immunity.

Conversely, it could be argued that mandatory vaccination can infringe basic human rights. The public may also end up losing confidence in the government if they are forced to vaccinate.

As the arguments for and against mandatory vaccination remain inconclusive, more compelling scientific evidence is required to support the ethical dilemma faced in such a scenario.

Pragmatically, mandatory vaccination is no guarantee that the vaccinated will be entirely spared from Covid-19, but it would be beneficial in reducing hospitalisation and shorter intensive care unit stay, which in turn would also be of great help to the overworked and burnt out medical frontliners.

The option and choice for an otherwise healthy individual to get vaccinated is still better than refusing the vaccine altogether.

Vaccination is not mandatory or compulsory in Malaysia but it is important to look at the issue from the perspective of the community and individual. The government should respect the individual’s autonomy and not be quick to impose paternalistic measures on the person, that would infringe human rights.

The government should consider other lesser restrictive measures that can ensure the preservation of the principle of autonomy:

1. Emphasise the educational approach by informing the vaccine hesitant population of the risks of not being vaccinated, while also addressing their concerns.

2. Use behaviour nudge techniques such as providing incentives or gift cards to encourage inoculation.

3. Clamp down on disinformation on social media that would further reinforce their false belief.

4. The Health Ministry should release data and statistics that are available to show transparency so the vaccine hesitant population can make informed decisions.

5. Teachers should not be allowed to teach in schools if they are not vaccinated.

6. Those who have been vaccinated can play a role by sharing their experiences. Social media influencers can use their star power to influence fence sitters.

7. The Education Ministry should consider setting up vaccination centres at schools, and provide counselling for school children who refuse vaccines.

In a nutshell, the government should navigate through this ethical dilemma cautiously.

If done properly, the lesser restrictive measures can achieve the same desired outcome of mandatory vaccination, while protecting the autonomy of the individual.

Comments: letters@thesundaily.com