ON Teacher’s Day this week, parents once again declared the quality of education in national schools as “pitifully behind times”, and questioned the deteriorating standard of the English language as well.

While English has been struggling to survive in the school curriculum, politicians continue to fight tooth and nail for Bahasa Malaysia to predominate, while blatantly minimising the usage of English.

Another parental concern was that world history was being slowly removed and instead replaced with rewritten politically-palatable histories to showcase local leaders. Even the use of English in mathematics and science was used as a political tool that experienced volatile changes.

In the late 1990s, an unspoken compromise was reached for the introduction of “a one language and a tunnel vision that propagated local history”. The approach manifested itself as a more information-based and spoon-feed education that was mainly exam orientated. Somehow, this system developed its own momentum with a justification of its own, and was perpetuated. Even the enforcers have lost sight of why it was there in the first place.

In 2012, Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin as the Education Minister then raised concerns over these issues and spearheaded the Malaysia Education Blueprint (2013-2025), which benchmarked better syllabus, teaching materials and internationally-recognised syllabuses in schools.

The blueprint also clearly defined language competency deficiencies and quality teaching expectations, with a guide for training English language teachers to raise the level of English proficiency. However, the essence of this extensively researched, detailed and comprehensive blueprint has been diluted and distilled in various transfers of powers over the last four years.

Meanwhile, more affluent parents, who can afford an exorbitant price for quality education, sent their children to international schools, which provided an insightful look into world cultures, histories and literatures.

The underprivileged monolingual national school child inherited the local, weak education practices and was forever left behind.

Students should be able to reimagine another bigger world which offers so much more that is already out there. This knowledge cannot be underestimated in today’s world. Our young people should be entitled to this learning.

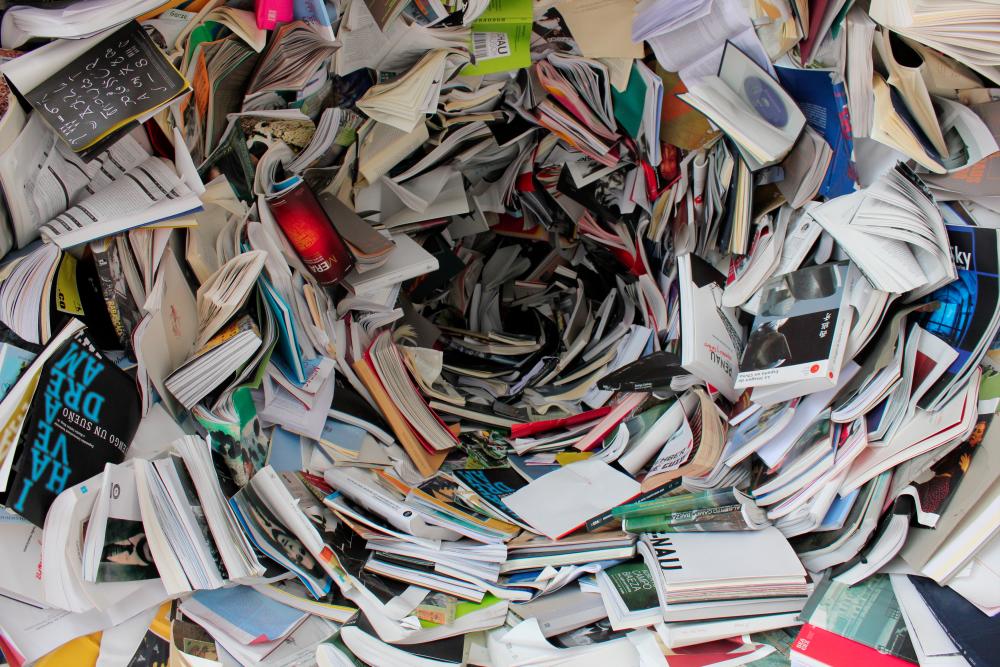

Many teachers who were only proficient in Bahasa Melayu could not access the millions of books in the world of English literature. Even if some of the books were translated, the beauty, the rhythm in reading and its exhilarating experiences will be lost in interpretation.

Great works of classic authors like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and George Orwell, which have stood the test of time, need teachers to be trained in special creative literature skills for subjective interpretation and intellectual discourse with their students. Teachers should be able to challenge students to a critical engagement of diverse opinions and provoke deeper levels of creative thinking.

Literary books give us insight to another history, culture, social and political reform, with students having a wider radar of what to read. Words in such literature have meaningful and timeless quotes that give students a broader view of life and a point of reference of their own standing in the global world.

An inspirational story to depict here is Alchemist, written by Paulo Coelho. It is about a boy who travels from Spain in search of treasure buried in Egypt. In his travels, he meets people, encounters obstacles and eventually discovers that knowledge is the real treasure.

Our social fabric has been built by many communities, ethnicities, literatures and is the home to 137 languages. Many of these indigenous languages were left unrecognised, with their voices and thoughts systematically and deliberately silenced to make way for Bahasa Malaysia. Tamil literature continues to be taught in secondary schools but after school hours.

In the past, the government used free Tamil literature books but in recent times, administrators have made it inconvenient for students to study or take literature as an examination topic, with excuses like “no funds, no teachers or no students”.

In the same way, reportedly Chinese literature was not popular among the students due to the lack of attention given to the subject.

World literature, reading and creative thinking should be made compulsory, not only for mastering languages but also in educating and preparing young Malaysians for vibrant changes and challenges of globalisation. The system should not deny young Malaysians these privileges.

Reading beyond school textbooks is essential for those who seek to rise above the ordinary student. We have to rebuild this broken system and motivate them to read about the historical events and great leaders who brought change in our world.

If they are limited to a localised tunnel-visioned reading, they may grow up in a toxic well of conjectures, where fiction and facts can be mixed up.

Comments: letters@thesundaily.com