Colonialism in The Malay Archipelago: Civilisational Encounters presents fresh perspectives on colonial incursions into the Nusantara region seen from the lens of the region’s scholars and researchers. They question motives and debunk biases in colonial and post-colonial narratives where native societies and indigenous peoples are depicted as inferior and in need of foreign intervention. Deliberately underplayed in these accounts are the selfish motives of Western imperialists and their agents including the colonial administrations and trading companies they established. Political and economic rivalry amongst them in Europe was the real driving force behind the colonial policies and strategies executed by Portugal, Spain, Holland and Great Britain that saw the expansion of territory and dominance in faraway places in their bid for “gold, God and glory” – the three civilisational motives of Christian Europe. The book’s focus as articulately described in the Introduction is the civilisational encounters between the colonialists and the colonised peoples.

Occidental romanticisation of the pioneering spirit and adventurous skills of European explorers camouflaged their hard-core objective of political and economic domination to reap power and profits via trade monopolies and administrative means, and inevitably through military aggression. The subjugation of peoples with long-standing cultures and civilisations to impose upon them western values and systems was to leave great imprints on the region’s history and modern development. The writers seek to uncover the various ramifications of colonial rule, among them economic, political, educational, socio-cultural and demographic.

The real politico-economic motive of Western colonialism is affirmed by Osman Bakar who gives documented chronological evidences of the Portuguese imperial vision and policy over the monopoly of the spice trade in Malacca, while Bondan Kayumonoso discusses intense Portuguese, Dutch and British rivalry over the nutmeg trade in Banda Islands. Anwar Ibrahim hits out at the “restrictive lens” of colonial authority which “describes, pigeonholes and pinions the history and being” of the society. Errors of interpretation in the accounts of British colonial writers denigrated the Malays, their culture and society and displaced a rich civilisation. Ahmad Murad Merican presents a scathing attack on the gross distortion of facts in colonial accounts of events where the occupation and secession of territories were rationalised as right and proper.

Islamic education, however, was allowed to continue in the pondok belt across the Archipelago inadvertently leading to positive developments for Malay identity and solidarity. Jajat Burhanuddin, Achmat Salie, Mohamed Abu Bakar and Awang Sariyan discuss the role played by Islam and the Malay language as the vehicle for civilisation during the Malay Sultanate which was to face some suppression when English secular education was introduced by the British. Although the native Malays in rural enclaves were untouched by Christian missionary work, non-Malays living in the town areas were under its influence and converted to Christianity.

In the Philippines, three centuries of Spanish rule ingrained strong Hispanic influences and led to greater conversion to Christianity among the natives. Their ancient Malay past was relegated to history as they became beholden to the civilisation brought by their Spanish colonial masters. Even the identity and images of native women and men were Hispanised by Spanish colonial writers according to Fernando A Satiago Jr, Maria Louisa T Camagay and Ian Christopher B Alfonso.

Mohd Nazari Ismail discusses the development of Islamic banking which has managed to skirt round the civilisational contestation between Islam and the West where the charging of interest for a loan or “debt for profit” was considered as haram. The introduction of bank loans in the western banking industry is now viewed positively as part of the modern economic system where Shariah-compliant Islamic Banking is suited to greater Malay-Muslim economic participation.

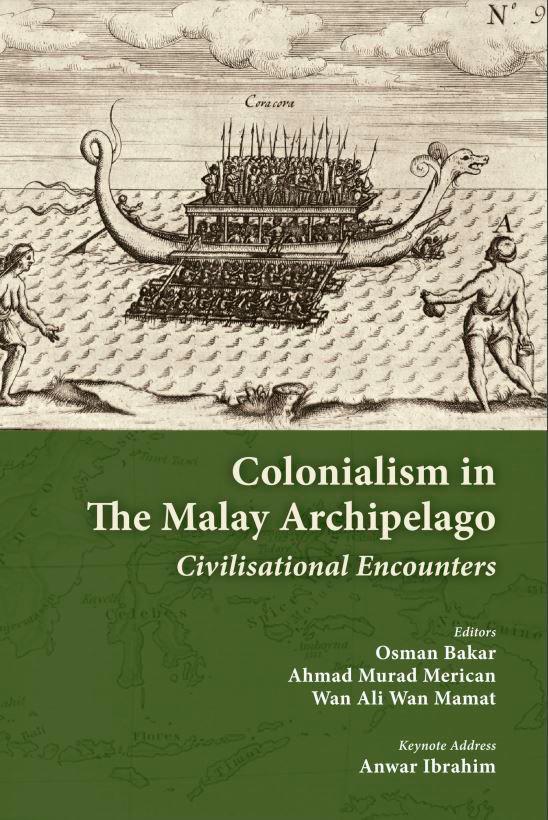

Of great interest are the chapters which question and debunk three outstanding myths about the natives of the Malay Archipelago perpetuated by their European subjugators, namely they were an uncivilised people, lazy natives and aggressive pirates. The writers challenge these myths with some authority, referring not only to alternative writings but more convincingly to reported errors of judgement and mistakes. Salleh Yapar endorses Alatas’ (1977) debunking of the myth of the Malays as lazy natives by referring to records of their “robust economic and social-cultural activities”, their skills as shipbuilders, navigators and traders in international commerce centuries before the arrival of the westerners when they had established enlightened civilisations such as Srivijaya and the Malacca Sultanate with its thriving entrepot and trade centres where the Malay language was the lingua franca. Far from being lazy they were admired by the ancient Chinese for being smart and diligent.

Farish Noor describes the East India Company (EIC) as the “original corporate raiders” in the colonial grab for territory in Borneo through agents such as James Brooke and Henry Keppel. What were long-established networks and arrangements between trading ports in the Malay Archipelago became the magnets attracting British colonialists who positioned themselves as saviours fighting against marauding Bornean pirates. These narratives were in fact written by members of the EIC intent on expanding their spheres of political and economic influence. Ahmad Murad Merican outrightly condemns “the act of colonialism itself as (is) a crime against humanity” and decries western-biased representations as distortions of the past which have buried the native self. He calls for investigations into the misdeeds of European colonisers and a total reexamination and reconstruction of the past to produce the right images of both the subjugators and the subjugated.

Much has been said about the ramifications of British colonialism in Malaya oscillating between praise for the institutions they established, and blame for their racially motivated policy of divide and rule. Much societal damage has ensued from the policy where the three major races were segregated by biased educational and economic engineering. The gaps and schisms are apparent to this day and are the cause of much attrition in inter-ethnic relations. Rather than deny British rule, it would be of greater historical significance to uncover the hidden truths about British colonialism in Malaya for more than 150 years.