THERE is a sense of social power in storytelling. Or, in other cases, not telling one’s story.

“Telling stories is a human instinct. As much as words can connect us, they can also divide us,’’ explains Ling Low.

Her latest short story Weeds, written during the first movement control order last year, is among 25 out of 6,423 entries shortlisted for this year’s Commonwealth Short Story Prize.

It is a tale of an old wealthy retiree who grows envious of the gardeners working on the grounds of his condominium during a national lockdown when he is forced to stay indoors.

Weeds underscores the power and struggle of our social class, particularly the often unacknowledged recognition of foreign workers who have taken up essential jobs.

“Stories are how we make sense of life. So, I write as a way of connecting with other people, in the hope that I can create something others find as meaningful as the stories I’ve read and loved,” said Low.

Like many writers, she started as an avid reader and over the years honed her craft in storytelling through journalism, filmmaking and writing short fiction.

“My reading patterns have shifted over the years. There was a point in my life when I was a full-time editor and journalist, and I actually stopped reading books. I think it was because I was always reading articles.”

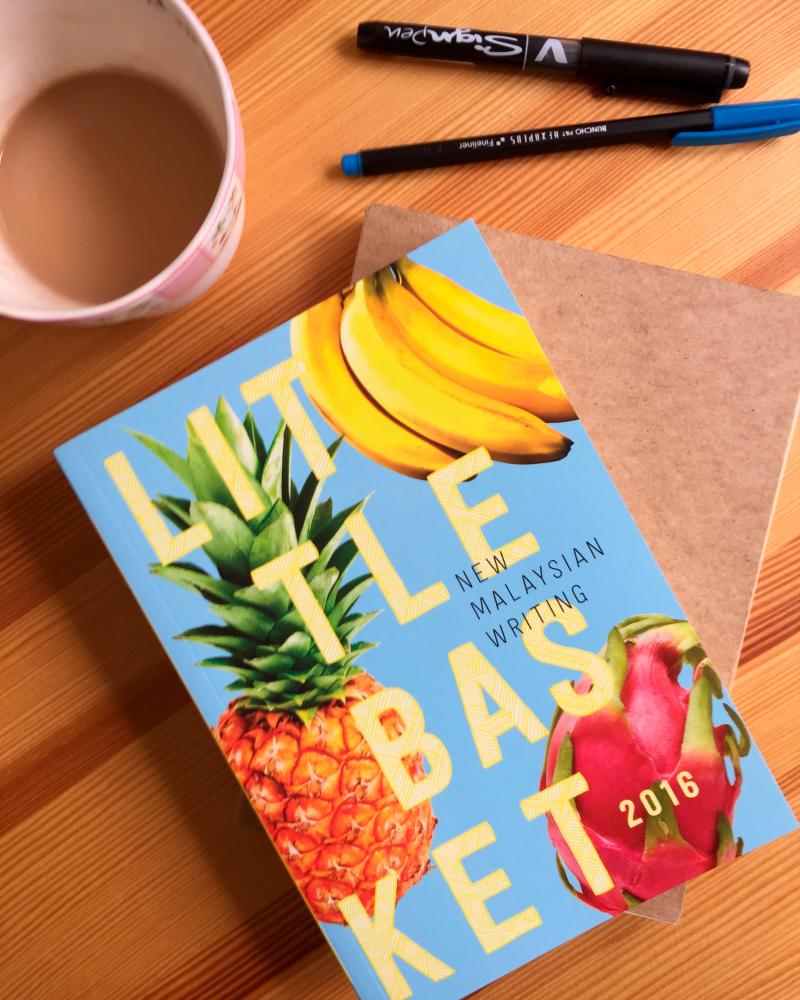

She has now rediscovered the pleasure of reading, and is devouring a wide variety of genres from novels, short stories to essay collections.

“I’m relishing this feeling of being mesmerised and surprised by writers again. Lately, I’ve been reading more from women writers, and also more from Asian or Asian diaspora writers.”

What was the inspiration behind Weeds?

For a long time now, I’ve been interested in how we are so interconnected and yet isolated. I suppose it’s part of the continuous tension of living in a big city. In KL, we’ve seen luxury developments sprout up right next to kampungs. In Sentul, there even used to be cows roaming around in the shadow of new condos. It’s hard to escape these contrasts.

But more recently, the pandemic has heightened my awareness of how differently people live and how much of our society, as well as the world at large, is unjust and unsustainable.

On a global scale, we’re seeing that with the way vaccines are being distributed (or not distributed).

But we’re also seeing it in our own neighbourhoods. For example, hospital cleaners have struggled to be recognised and compensated as frontline workers.

Courier delivery drivers had their pay rate cut during one of the busiest periods for deliveries. And migrant workers, who fill many key jobs, are too often forced to live and work in cramped, dangerous conditions.

That said, I would describe Weeds as a story that takes a slightly comedic approach to the situation we’re in. It’s about isolation, social class and power, but with a twist on the anticipated dynamics.

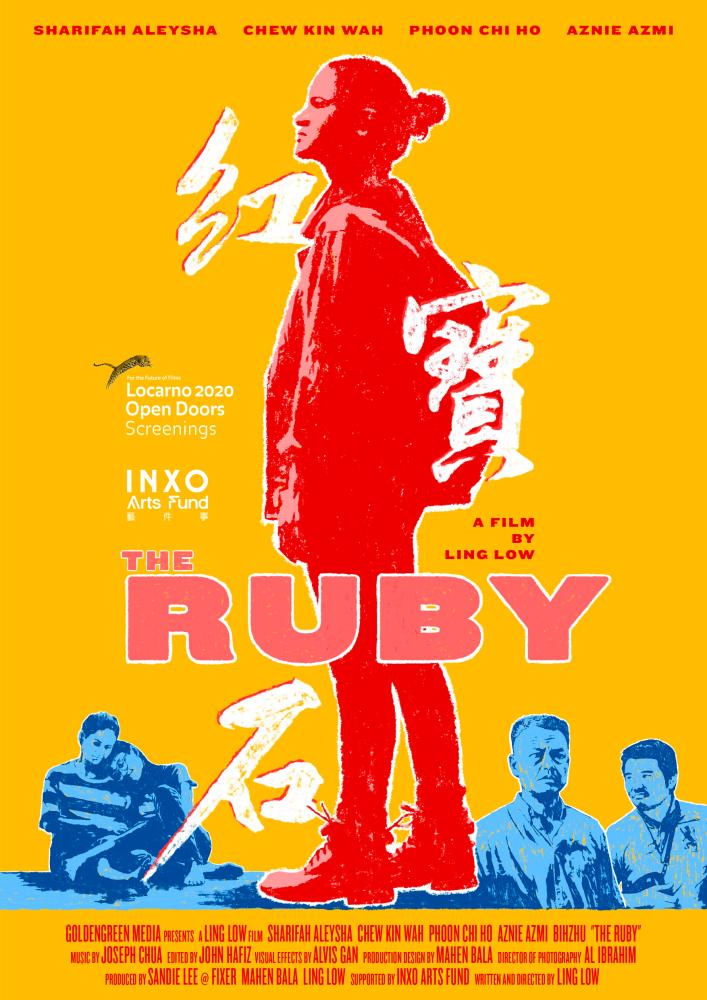

Your film The Ruby alluded to an ‘under-represented’ narrative, was that an active inclination?

To be honest, I don’t set out to tell “under-represented stories” because I can’t do justice to representing anyone or any group. All I hope to do is tell very specific stories and to find some sense of the universal in the specific.

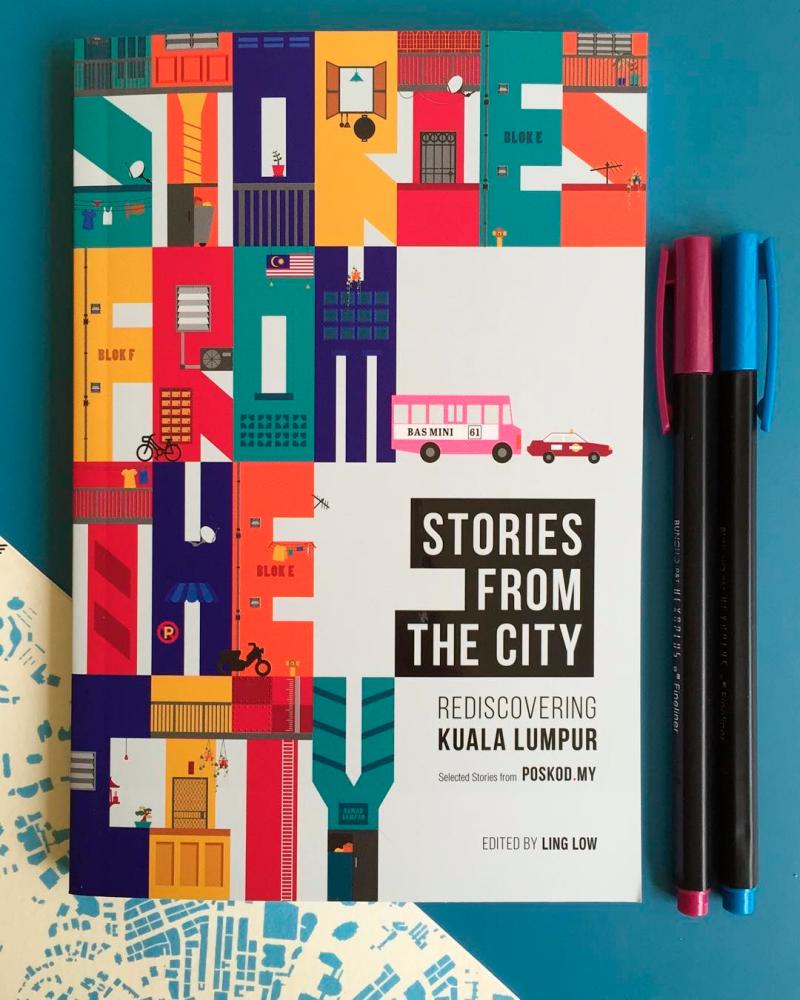

I do try to observe and draw on the realities of KL. I think that’s why I keep returning to narratives that have some shared sensibility.

In retrospect, I’ve been trying to chip away at the glossy, tourist postcard image of KL in order to see the grubbier but more interesting picture underneath.

Without realising it, I look for layers. In The Ruby, it’s the layers of a building’s past and the layers of communities who live in Chinatown. In Weeds, it’s the layers of social class and behaviour that separate the ivory tower from the ground outside.

How much of your personal experience influences your work?

Some of my stories draw more on my personal life than others.

For example, I once wrote a story about a family living in an underground bunker. That came from something that resonated with me. I guess we can’t escape ourselves in the process of creating work. Let’s say we walk into a room and observe something, there’s a reason we observed this thing and not that thing. Our taste shapes our perspective, and then our perspective shapes our taste, and it goes on.

But what’s shaped my outlook more than anything else, is that I have felt like an outsider throughout my life. In order to feel like I could fit in, I became hyper-conscious of other people. That makes me wonder about how other people think and feel, and those imaginings are the basis for various stories I’ve written.

Do you think you make a better listener or storyteller?

I think the best storytellers are great observers of human behaviour and they also have an ear for how people talk. As a writer, I believe it’s important to develop the skills of observing and listening. The other crucial thing is to read widely, especially the work of writers who are far better than oneself, in order to learn from them.

How do you critique your own work?

Slowly and painfully! I accept that it will take me several drafts – sometimes many, many drafts – to get to a place where I’m happy with what I’ve written. Sometimes, I show a trusted friend and fellow writer.

Often, my husband reads a draft too. I’ll get some feedback and then go on from there. I’m also in an international writers group that meets online.