Meg Jing Zeng, Queensland University of Technology

“So much smog here, how can we see the rainbow?” @Melody commented on Weibo – China’s micro-blog site – following Taiwan’s ruling on same-sex marriage.

On May 24, Taiwan’s constitutional court ruled that same-sex couples have the right to legally marry, becoming the first place to do so in Asia. The ruling was an encouraging sign for LGBTQ communities in the region.

But for the 70 million LGBTQ people in neighbouring China, the news was bittersweet.

Homosexuality has been legal in China since 1997, and the first proposal to legalise same-sex marriage in the country was submitted to the National People’s Congress meeting in 2003. Even though the proposal failed to pass on three occasions, the fight for marriage equality continues to be carried out by other activists.

While many were still rejoicing about the news from across the Taiwan Strait, the country’s most iconic lesbian social media platform Rela (热拉) was shut down on May 26. No official explanation for the shutdown has been given by Chinese authorities.

Outrage among the Chinese LGBTQ community

The shutdown led to widespread outrage among LGBTQ communities in China.

As Weibo user @momoda wrote:

6th day after the app was shut down, I still feel like a lost child without her family. Rela made me feel that I didn’t need to be scared that I was lesbian and I could be accepted by others... Now the world is dark again, I miss Rela

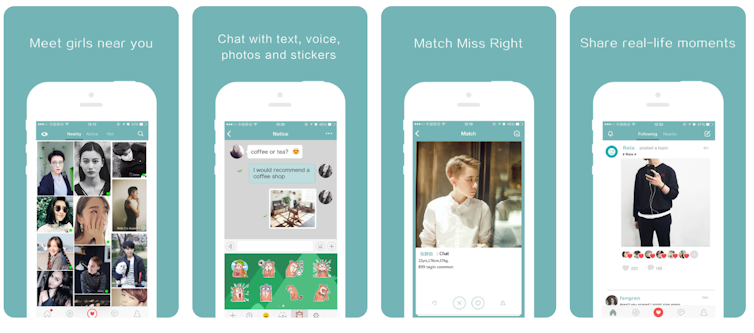

Formerly known as The L, Rela was founded by a Shanghai-based start-up in 2012. According to an interview in 2016 with its founder Lu Lei, Rela has over 1.5 million monthly active users, with 10% from overseas.

Although Rela is commonly described as a dating app, it is much more than just a “Tinder for lesbians”. Besides its match-making function, for instance, Rela contains a video streaming platform, where select users can share live broadcasts with their followers.

Rela is also a media content provider. From 2015, Rela has produced a number of lesbian-themed short films and even a sitcom.

Although homosexuality is not forbidden in China, same-sex romances still cannot be shown on national television under a set of new media rules. In order to avoid domestic censorship, Rela decided to launch its movies only on YouTube and on its own App, as revealed by its co-founder Wu Wenqing.

To its users, Rela’s success in China signified a certain degree a greater acceptance of LGBTQ people in the country. That’s why its sudden shutdown has been met with so much sadness.

China’s same-sex marriage campaign

Despite the shutdown of Rela, both academics and activists take an optimistic view of the development of China’s LGBTQ rights.

Sociologist Li Yinhe, as well as researcher of Chinese politics Timothy Hildebrandt, for instance, make the argument that thanks to the lack of influence of religious institutions in the country, the cultural resistance to legalising same-sex marriage in Chinese society is relatively low, even compared to Western countries.

As the influence of China’s millennials grows, social attitudes continue to shift. LGBTQ people in China are also becoming increasingly vocal in society, partly due to the country’s fast development of information technologies and its emerging “pink economy”.

In recent years, social media has played its its part in the same-sex marriage debate. In 2016, 1.5 million views were registered by a social media campaign on Weibo, which encouraged gay people not to bow to family pressure to enter into sham marriages.

A key catalyst for the discussion of marriage equality among the Chinese public has been the country’s tongqi (同妻) phenomenon. Tongqi is a Chinese term used to describe women who marry gay men.

In 2012, Luo Hongling a 31-year-old professor at Sichuan University, committed suicide after her husband came out as gay. The news brought public attention to the phenomenon of LGBTQ people being forced into heterosexual marriages by social pressure. And this triggered public discussion about the need for same-sex marriage.

According to recent estimates, there are over 16 million tongqi in China, and they are now an emerging force pushing for the legalisation of same-sex marriage in the country.

Pressure from across the strait

The new ruling on same-sex marriage in Taiwan is significant to LGBTQ activism in China. As Li Yinhe, the country’s most vocal academic advocating same-sex marriage, points out in a recent interview:

In the past, when we talk about those Western countries who allow same-sex marriage, people disagreeing with the idea would use excuses like: Western countries have a different sex culture, and they have different customs. However, if the new rule is passed in Taiwan, with whom we share the same culture and ethnicity, it will demonstrate that same-sex marriage can be accepted in Chinese society

But to Chinese authorities, the pressure from Taiwan’s new ruling is more than social, it is also political. Internationally, Beijing is strongly defending its One China policy and expanding its influence in the region. Taiwan’s position as the new leading force in LGBTQ rights in the region reflects poorly on Beijing, especially in light of its dubious human rights record.

Domestically, Taiwan’s democratic political system is often portrayed as chaotic and malfunctioning by Chinese media.

The Tsai Ing-wen administration is demonstrating Taiwan’s democracy can be well functioning, especially with regard to advancing the human rights of its citizens.

As @danyi wrote on Weibo after the shutdown of Rela, “Taiwan won the right to have same-sex marriage, and the mainland lost its app for lesbians. For the first time I’ve realised that Taiwan is better than us.”

![]()

Meg Jing Zeng, PhD Candidate, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.