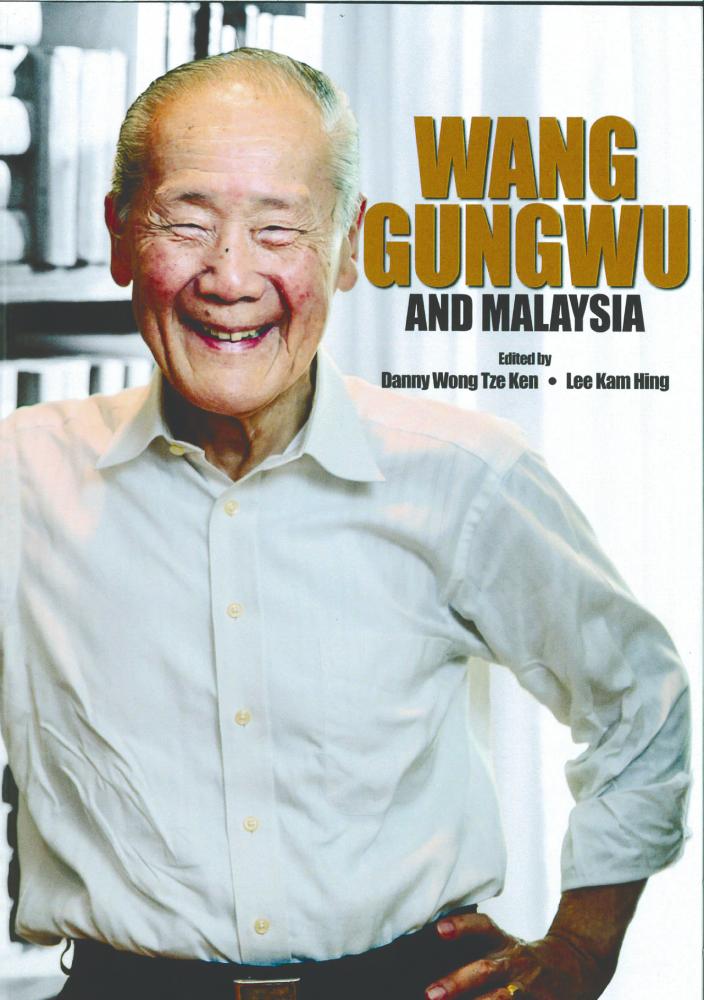

The book, Wang GungWu and Malaysia, is a collection of 16 essays by established scholars, who were former students and colleagues of Professor Wang GungWu, in honour of his tremendous contributions to scholarship.

Reading this book, one gets an appreciation of Wang’s multi-faceted talents.

Wang was not only an eminent scholar but a public intellectual and an able administrator who built up the History Department in the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur, the Far Eastern History Department in Australian National University and East Asian Institute in the National University of Singapore, not to mention his stint as the vice-chancellor at Hong Kong University.

The essays can be grouped into four areas: personal accounts of interaction with Wang, his writings on and brief participation in Malaysian politics, his pioneering works on overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia and Nanhai trade, and on international relations in particular the interpretation of China and Chinese to the world from an Asian perspective.

Khasnor Johan, Lim Teck Ghee, Stephen Leong and Anthony Reid provide interesting personal recollections of their relationship with Wang and the influence on their professional lives – be it launching Khasnor into the study of Malaysian history, or Anthony to be a Southeast Asian historian and Lim to be a scholar who speaks truth to power.

Their overriding consensus is Wang is the embodiment of a gentleman-scholar – a brilliant intellectual who, is at the same time humble, puts you at ease, encourages rather than intimidates.

But Wang is not the typical image one has of an academic historian buried in a library digging into the past.

He studies the past to understand the present and is engaged in the construction of the future. He is not isolated in an ivory tower.

Having lived through tough times – Japanese invasion of Malaysia, revolution in China, anti-colonial struggles in Malaya and Singapore – he was involved in post-colonial efforts at nation-building in Malaysia.

This is well captured in the essays by Lee Kam Hing and Mavis Puthucheary.

It is most likely that his personal friendships with Dr Tan Chee Khoon and James Puthucheary, going back to their days at the University of Malaya in Singapore, and his concept of Malaysian nationalism as consisting of “a nucleus of Malay nationalism enclosed by the ideal of Malay-Chinese-Indian partnership” disposed him to play a role in the formation of the Gerakan Party, a non-sectarian party, in 1968, just before he left for Australia.

Wang was a trail blazer in his studies on the Nanhai (Southern Sea) trade and overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia which became standard references on these subject matters.

Chinese maritime expeditions to Southeast Asia in the 15th century led to the first migration of southern Chinese into Malaya and other parts of Southeast Asia.

Wang, himself an overseas Chinese, was among the first to study in depth the Chinese immigrants’ experience, the challenges they face in acculturation and building their identity in their new homes as explored in the pieces by Tan Chee Beng and Danny Wong.

Taking a cue from Wang’s study on the Southern Sea, Leonard Andaya, Loh Wei Leng and J K-Wells expanded their investigations into other aspects of maritime trade.

Andaya examines how various communities, such as Southern and Northern Chinese, and Malay seafarers construct different concepts of seas and oceans and how these impact on their lives.

Both Loh and K-Wells explore how the Malacca Straits played and continues to play an important part in the migration, trading and political activities of Chinese and Southeast Asians, from ancient time to present day.

The essays of Peter Chang and Anthony Milner demonstrate the significance of Wang’s work for international relations.

For Milner, Wang’s area studies approach provides an antidote to the Western dominated view of international relations which eschews culture and history in favour of positivism and assumption of universalism.

According to Peter Chang, China for the most part was an inward-looking nation, content to leave the rest of the world (mainly the Western world) to interpret the “real” China.

Steeped in Chinese and Western education, Wang and Tu Wei-Ming are among the pioneers to interpret China to the world from an Asian perspective.

This is all the more cogent given China’s recent rise as a major economic power posing challenge to US supremacy.

Throughout history, such Thucydides moments are fraught with conflicts and dangers.

How both parties view and react to each other is crucial in determining the outcome of the competition.

Peter Chang sees “the pivotal significance of Wang’s life and work, namely, to help mitigate the trust and perception deficits between the Chinese and the American world”.

Barbara Andaya notes that Malaysian historiography has made great strides since Wang’s childhood days in Ipoh.

Her own work and that of other local historians on the history of Ipoh and the Kinta Valley, and Abu Talib Ahmad’s work on Pahang are testament to that.

Finally, Philip Koh, a lawyer, ponders how historians and lawyers interpret “facts” and “truth” illustrated in the legal case of Public Prosecutor vs Mohd bin Sabu (2017).

In summary, for a reader interested in Wang, this edited volume of essays is a useful introduction to the broad range of his work and achievements and also offers a glimpse of him as a teacher, scholar, friend and caring person.

It is a fitting tribute to one of Malaysia’s finest intellectuals.

Comments: letters@thesundaily.com