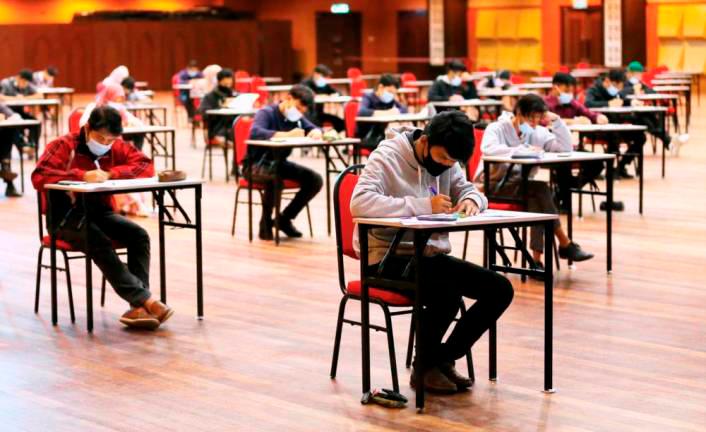

Learning has been disrupted for our children as schools are closed as part of strategies to fight the coronavirus.

School closures since mid-March 2020 have suspended physical classroom learning for about 4.9 million students in pre-, primary and secondary schools nationwide.

Instead, teaching and learning have been delivered through a combination of alternative channels, online platforms mainly, but also television programmes, phone calls, texts and handouts.

Despite these efforts, concerns on learning losses remain. This article discusses how distance learning during the pandemic exacerbates inequality in education.

Education inequality before the pandemic

Educational inequality has existed prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

For example, in 2014, the percentage of children in the bottom income quintile (B20) out of school was 4.6%. Conversely, only 1.4% of children in the top quintile (T20) were out of school.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) “identified (school affordability) as a major cause of inadequate pre-school and upper-secondary enrolment rates”.

On top of monetary barriers, certain populations face other disadvantages. For example, there are reports of schools, especially in rural areas, lacking basic facilities and having dilapidated conditions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, differences in access to and quality of education have been linked to differences in student achievement.

In 2011, the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia school grade average for urban students was 8% higher than rural students.

Learning issues during the pandemic

Within this context, the Covid-19 pandemic and shift to distance learning have dramatically exacerbated education inequality in multiple ways.

Globally, over 60% of distance learning strategies rely exclusively on online platforms, however the digital divide – the differences between groups’ access to technology – creates an additional barrier to education.

Based on a survey by the Education Ministry involving 900,000 students, 37% of students do not have any appropriate devices.

Even if a household has an appropriate device, large households will have to share this device with multiple household members for study, work and leisure, emphasising the need for digital inclusion.

Good internet connection is also a necessary prerequisite. Although the national mobile broadband penetration rate per 100 inhabitants was approximately 120% in quarter 1, 2021, the fixed broadband penetration rate – which provides faster and more reliable connectivity – was only approximately 39% per 100 premises.

Furthermore, there are stark disparities by location as rates are lower in Kelantan, Sabah and Terengganu and higher in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor.

Aside from inadequate equipment and infrastructure, unconducive environments and stay-at-home orders complicate the adoption of distance learning.

A Unicef survey of 500 parents in 16 low-cost flats in Kuala Lumpur conducted from February to March found that 83% of respondents want their children to return to school, citing lack of space and inability to supervise children as parents/carers must juggle work, household chores and care work as key challenges in distance learning.

Also, while parents, students and teachers may be more familiar with these technologies a year after the onset of the pandemic, without data, we cannot rule out the possibility that some may still struggle.

In line with this, emerging issues from distance learning affecting children’s well-being such as social isolation, cyber bullying and child exploitation online must be considered in policies.

Learning losses and long-term challenges

Despite collective efforts to ensure a smooth learning process, the latest evidence from Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom shows that school closures have resulted in learning losses.

In the Netherlands – which provides a “best-case scenario” as the country closed schools for a relatively short eight-week period and has strong infrastructure for online learning – researchers found student performance on a national exam declined by three percentile points or equivalent to one-fifth of a school year, with the effect being 60% larger among students from disadvantaged homes.

Early findings conform to assumptions that learning losses happened during the pandemic and these losses are much larger for disadvantaged students.

One contributor to these uneven learning losses is wealth. More affluent families are more likely to have the technology, connectivity, books and general capabilities including money, skills and time to support their children’s learning.

In contrast, the concurrent economic downturn during the pandemic makes it harder for poorer parents to finance their children’s education, jeopardising their children’s education prospects.

As educational attainment is a determinant of productivity and income, the unequal effect in learning losses may also contribute to worsening income inequality.

The impact on inequality transcends income and touches broader dimensions such as gender and children with disabilities.

For instance, gains in gender equality could be set back by the pandemic as women have been found to be disproportionately affected in taking up household and care work, and in more extreme cases, fall prey to domestic violence, child marriage and early pregnancies, contributing to higher dropout rates among women.

Self-learning materials online or through handouts may be inaccessible to children with disabilities who need specific support.

These differences in educational opportunities and subsequent learning outcomes have long-term implications, with the poor, vulnerable and marginalised getting the short end of the stick.

Conclusion

Given the abruptness of the situation in early 2020, the government, parents, students and teachers were understandably unprepared for the transition to distance learning and were forced to adapt.

One year later, it is clear that the situation may not revert to pre-pandemic ways and the education sector must not only compensate for learning losses but also accommodate the “new normal”.

The government has recognised some of the aforementioned issues and provided relief by providing devices and internet for disadvantaged students, educational content on television and online, and upskilling/training for teachers.

Granted, more must be done as these current measures are rife with their own issues and several avenues remain unexplored.

One practical option the government could consider is to implement wide-reaching learning recovery programmes such as an intensive tutoring programme to ensure young children are able to master reading, writing and counting skills before moving forward.

These programmes should aim to help students who have fallen behind to catch up.

Importantly, the government must learn from this pandemic, recognise the gaps in the education system and build back better to be better prepared for future crises.

It is vital to build a system that can make better use of hybrid learning which utilises a mix of in-person and distance learning.

There are different models of hybrid learning, but its main feature is its flexibility and it has the potential to promote inclusive education by understanding the learning environments of and support needed by different groups.

If done correctly, we can make up for learning losses in this generation of students and ensure future generations don’t fall behind in the face of similar crises.

Jarud Romadan Khalidi is a researcher at Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) and Grace Loh Wan Chi is a student at London School of Economics (LSE) currently interning at KRI. The views are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the official position of KRI. Comments: letters@thesundaily.com