THE recently concluded Malay Dignity Conference digressed greatly from the concept of racial unity envisaged by our forefathers. I believe if Tunku Abdul Rahman, Tun Sambanthan and Tun Tan Cheng Lock were alive today, they would be appalled at the way the nation is heading.

However, it is not my intention to criticise the participants of the conference for claiming a perceived loss of dignity. Rather, I wish to approach the notion of dignity from a historical perspective.

In Malaysian history, dignity in as far as it means a state of being worthy of respect, was rightfully earned when a historical figure upheld ethnic inclusiveness.

Indeed, there were a number of historical personalities who played inspiring roles transcending racial barriers towards the building of our country.

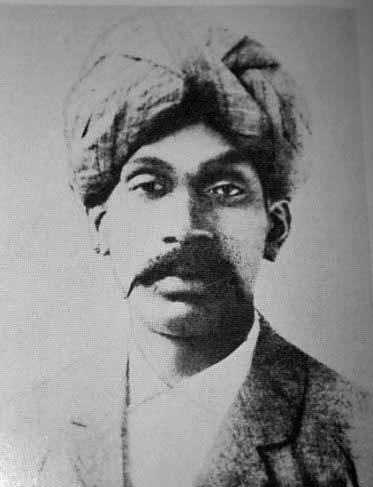

One such personality is none other than K. Thamboosamy Pillai, who was highly regarded by the British as a “friend of every man”.

He was greatly respected among the British administrators and members of all the other races (Europeans, Malays, Chinese and Indians) who liaised with him in Kuala Lumpur between 1874 and 1902.

It was the period when the British had just officially intervened in Malaya, and here was an Indian who rose to become a role model for the British and the Asian immigrants.

What is even more astonishing about Pillai is that he, an Indian of Tamil origin, would be highly regarded by British administrators at the time when Asians were not treated on equal terms.

It is an amazing feat that he was able to build an impeccable reputation and to eventually become a leader of the Indian community in Kuala Lumpur. British administrators like J. H. M. Robson, J. G. Davidson, J. M. Gullick, W. E. Maxwell, Frank Swettenham and others had high respect of him. He was seen as a big-hearted man who believed the wealthy should be charitable.

To quote J. M. Gullick, “To Thamboosamy money was not everything: it was a means to an end, something that should be expanded. He did much good with it and had the respect of every community.

“He is still remembered as the type of man we need today, hospitable, generous to a fault, and kindly, who devoted his wealth and talents to good-fellowship”.

Owing to his English fluency, Pillai proved to be an able administrator. He was appointed by J. G. Davidson, the first Selangor resident, as the state treasurer several times and was primarily tasked to review financial plans and sanction funds for development projects in Kuala Lumpur. Before entering into a business relationship with Loke Yew, a prominent tin magnate, Pillai had also served as the acting state treasurer.

He was also one of the founders of the Selangor Club, a renowned European club in the Federated Malay States, and in the late 1880s and 1890s became a very active committee member.

His close relationship with prominent Europeans is evident when he would often invite them for curry tiffin at his house on Batu Road. Many leading men of the time attended the lively parties he threw.

Among them were Captain Talbot (Commissioner of Police, Federated Malay States), Colonel Walker (Acting British Resident Selangor, 1899), W. J. P. Hume (Warden of Mines, Selangor), Charleton Maxwell (son of British High Commissioner, William E. Maxwell), E. V. Carey (Chairman of the United Planters’ Association of the Federated Malay States), A. B. Voules (Federal Inspector of School, Kuala Lumpur) and many more.

Pillai was also sent to India by the government to recruit labourers to work on railway construction and public works.

He was subsequently appointed to the Indian Immigration Committee in 1900 and is said to have brought into the country some of the earliest Indian labourers to have ever worked in both industries.

In his capacity as the Visiting Justice – to which he was appointed in 1885 – he was able to observe and sympathise with the plight of the Indian workers.

His ability as an administrator is further seen when in 1895 he was appointed as a member of the Sanitary Board Kuala Lumpur (SBKL) along with other prominent Indians such as Doraisamy Pillai, Chellapa Chetty and Pariaman Pillai.

However, unlike the others, Pillai was more outspoken and very vocal in his views on issues concerning the development of Kuala Lumpur.

He served as the committee member of the Electric Board of Kuala Lumpur and was instrumental in providing electricity for the city. As a member of SBKL, he also sought to establish for the Indian community a settlement akin to the Malay Agricultural Settlement.

Pillai’s role as entrepreneur began when he resigned from his capacity as government official in 1889. Following that, he ventured into road construction/contracting business, estate and mine management and even into property businesses.

As a road contractor, one of his most notable contributions was the building of a road connecting Kuala Lumpur with Rawang and is said to have completed it by using bullock carts. Its construction not only led to the influx of workers from outside the city but also stimulated the economic growth of Kuala Lumpur.

In the plantation industry, Pillai reportedly owned some 500 acres of coffee plantation in Selangor in 1890. Most of the plantations were located in Klang. He also became a member of the Selangor Planters’ Association on Feb 17, 1893.

It is interesting to note that only he and Loke Yew were the Asian members of the exclusively European association. Pillai and Loke Yew in fact established joint ventures in the tin mining business in 1893 when both formed the New Rawang Tin Mining Company. Together they pioneered the usage of electricity for mining purposes in the country.

Pillai not only drove Loke Yew to open large-scale mining concessions by introducing him to prominent Chettiar money lenders but himself also invested in other sectors such as railway management. He invested profits gained from these ventures into his property businesses.

Pillai also contributed to the establishment of Victoria Institution in 1893. He realised the importance of English education which would enable the locals to be recruited in the civil service (for subordinate positions). He along with Loke Yew and Sultan Abdul Samad contributed 1,100 dollars each for the construction of the institution. Pillai was one of the first Board of Trustees of the school.

The Indian community of Kuala Lumpur benefited immensely from Thamboosamy Pillai. He looked after the welfare of the Indian labourers recruited for public works by ensuring that their pay was commensurate with their labour.

While serving as the visiting justice for the Kuala Lumpur jail in 1885, he assisted the magistrate to assess cases involving Indians. He also strove to introduce modern Western medicine to the Indian community especially considering the spread of cholera, beri-beri and smallpox in Kuala Lumpur at that time.

Pillai was also the founder of what is known today as the Sri Mahamariamman Temple in Kuala Lumpur along Tun H. S. Lee Road.

The temple was originally established as a family shrine but was later opened to the public in the late 1920s.

Interestingly enough, the temple’s official opening to the public was officiated by the Sultan of Selangor. The Thaipusam festival celebrated by the Tamils to commemorate Lord Muruga has been celebrated in this temple since 1892.

He was also responsible in promoting Batu Caves as an important Hindu shrine. In 1890, he erected a statue of Sri Murugan Swami inside Batu Caves and is also said to have contributed 150,000 dollars to the development of the temple.

Besides that, Pillai also promoted the development of Tamil education. He even used his residence along Batu Road (now, Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman) near Bilal Restaurant as an institution to teach children of the Tamil labourers living in Kuala Lumpur.

Thamboosamy Pillai was also very popular among the Malays. He was said to have known their language and culture well. As a philanthropist, he assisted many financially, especially during festive seasons and for personal needs.

He also generously donated money for Malay weddings together with gold rings and livestock such as chickens, ducks, goats, and buffaloes.

It is obvious from the many roles played by Thamboosamy Pillai that he was a Malayan at heart and was serving everyone irrespective of race in Kuala Lumpur.

He helped British administrators who needed his service, the Chinese when they needed a connection to the government, an entrepreneur like Loke Yew for financial support from the Chettiar community and the Indian labourers and Malays in Kuala Lumpur.

The British administrators rightly captured this in the following way:

“In the orchestra of Malayan life there are many instruments, the big drum of rubber (Indians), the quieter violins of rice and kampong agriculture (Malay), the strident trumpets of tin and the insinuating clarinets of finance (Chinese).

“All must be played in tune to make the orchestra a band of brothers. Thamboosamy sounded the first notes and was not the least of those pioneers who have made Malaya actually great and potentially greater”.

What we all could remind ourselves from time to time from Pillai’s history is that all of us are Malaysians and there will be a great sociopolitical cataclysm if we were to see the others (especially the non-Malays) as orang asing.

The more important take away from his story is that dignity need not necessarily be an inherent right but something that has to be earned, as Pillai did through his professionalism and benevolence.

The sponsors and those who attended the Malay Dignity Conference should realise this and think how they could play a role to forge inter-ethnic cooperation, like Thamboosamy did.

Associate Professor Dr Sivachandralingam Sundara Raja is with the Department of History, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, University of Malaya. Comments: letters@thesundaily.com