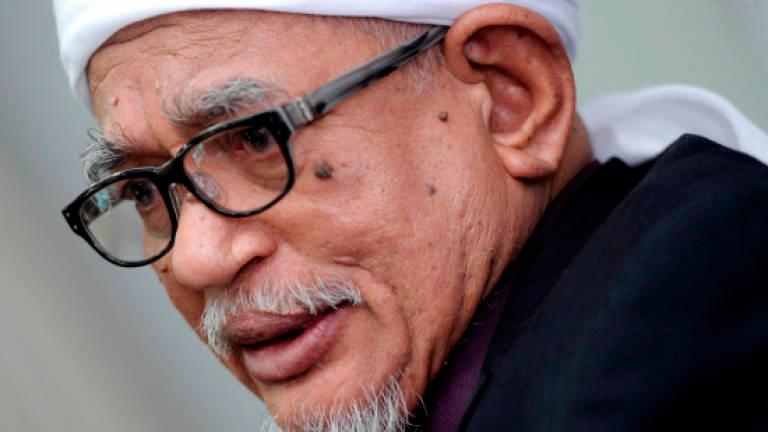

NO other political leader has ever written such a long Facebook tract on corruption as PAS president Tan Sri Abdul Hadi Awang(pix).

In his Aug 20 posting, he roundly condemned the givers, receivers or middlemen involved in the practice of corruption.

“All parties involved in corrupt practices are grossly guilty,” Hadi Awang wrote.

“Therefore, all groups involved in corruption should be eliminated.”

It was a commendable sermon, except for one statement near the midpoint of his roughly 50-paragraph dissertation.

In recommending that action be taken all the way down to the root he remarked that among the biggest groups damaging the country’s politics and economy, “majoritinya daripada kalangan bukan Islam dan bukan bumiputera” (the majority are from non-Muslims and non-bumiputras).

In singling out non-Muslims and non-bumiputras, did he foresee a storm of protest stretching all the way to Borneo?

However, what is more worrying than a single episode is that many politicians lack the realisation that in a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multi-religious setting they need a sense of globalism to be leaders.

Instead, if they encourage their voters to maintain a deadly sense of exceptionalism and superiority, they may be subverting the prime minister’s lofty concept of Keluarga Malaysia and Keluarga Dunia, wherein all ethnicities and religions are treated as part of one Malaysian and World Family.

We must not assume that a person is less inclined or more inclined towards corruption purely on account of his religion.

Such an assumption demonstrates ignorance that all religions propagate exactly the same ethical standards.

Any variations are due to cultural and geographical adaptations, socio-historical contexts and differences in theological interpretations of sacred verses.

Even when there are dissimilarities, you need only to zoom out to the larger picture to realise the uniformity.

As an example, one religion forbids pork but permits beef. Another religion forbids beef and permits pork. There are also religions that forbid all meats.

The common value is that you must be sparing in meat intake, and preferably abstain from meat since it involves the killing of animals.

The same value ranges along a continuum, with restrained meat consumption at one end and total meat abstention at the other.

With climate change, trends now favour meat abstention.

As for corruption, which non-Islamic religion permits it? Let us take Buddhism as a standard bearer as it is the largest non-Islamic religion in Malaysia.

You may be familiar with Pancasila (the Five Precepts), as this Sanskrit term has been adopted by Indonesia to embody the nation’s foundational principles.

The second precept of the Buddhist Pancasila states: Adinnadana veramani sikkhapadam samadiyami (I undertake the precept to refrain from taking what is not rightfully given).

Any form of unlawful transaction, including theft, bribery, corruption, burglary, forceful acquisition of property and fraud, is covered by this precept.

The Buddha didn’t just lay down precepts. In the Anguttara-Nikaya, he warned against the danger of devotion to a leader who has fallen into error and been thus censured. His followers, in their complete devotion to him, will then stray from righteousness themselves.

However, leaders who stoke religious feelings of superiority may fall back on the claim that only their religion, being modern, offers a complete set of guidelines for living in society. But any such claim is again based on ignorance.

Two thousand years ago, the Dharma-sastra of Manu devoted 12 chapters to a stunning range of subjects, including rules of marriage, hospitality and law, in the juridical sense.

Dharma-sastra provided Indian society with a code of morality governing everything.

Promoters of religious exceptionalism – that their religion is exceptionally good and unique – ignore the calamitous downside when they utter the now familiar “we will defend your faith” chant.

Across the length of Asia from the Mediterranean to Pacific, ultra-traditionalists in several religions shout this chant with shaking fists accusing other religions of being a threat.

The religious labels differ, but the devastating consequences of sectarian play are the same in fuelling violence.

Religious identity must never be used to measure one’s worth to a nation.

Governmental vigilance is needed to sustain pluralism to ensure that the sense of globalism isn’t washed away by a tide of bigotry.

Elementary misconceptions should be addressed by dealing with the root of the problem.

Three months ago, the nation had to endure a tiny storm over claims that a popular Japanese cultural festival contained elements of Buddhist rituals that could lead you away from your own faith.

No one asked the key question: are Buddhist rituals fundamentally different from the rituals of your own religion, whichever that may be?

Do religions differ greatly in their rituals? On the level of specifics, yes. In terms of purpose, no.

What is the function of a ritual? Is it a ticket to secure afterlife pleasures?

This would mean that you regard heaven as a Disneyland.

No, the function of a ritual is to act like an adhesive that keeps all the tiles in your living room tightly bonded.

When every member of a community observes the same ritual, the community is tightly knit. Let’s take one example: the ritual of fasting.

Fasting may be daylong for a month, on full and new moon days every month, during Lent, abstention from meat for 250 days, one vegan meal per day for the 40 days of Advent and non-eating after lunch.

The variations in fasting types do not matter, what does matter is that everyone in the same community practises it and is keenly aware that the sacrifice is intended to improve your character and health, as well as strengthen community bonding.

On the other hand, if you diligently observe the fast but regard with contempt the styles of fasting practised in other religions, you fail to improve your character. Your fast has no moral value.

An authentic ritual may, however, be pirated and twisted to serve immoral goals. The ritual of tithing encourages you to contribute a minimum 2.5% to a maximum 10% of your gross earnings to ensure community well-being.

It’s an early form of income tax. But if you hike up a project cost to slice off 10% as “tithe” to secure approval for a contract, that ritual is known as corruption.

While an authentic ritual binds a community to a standard of moral behaviour, a perverse ritual has the opposite effect in loosening the bonds of morality, eventually leading to the breakup of that community.

The writer champions interfaith harmony. Comments: letters@thesundaily.com