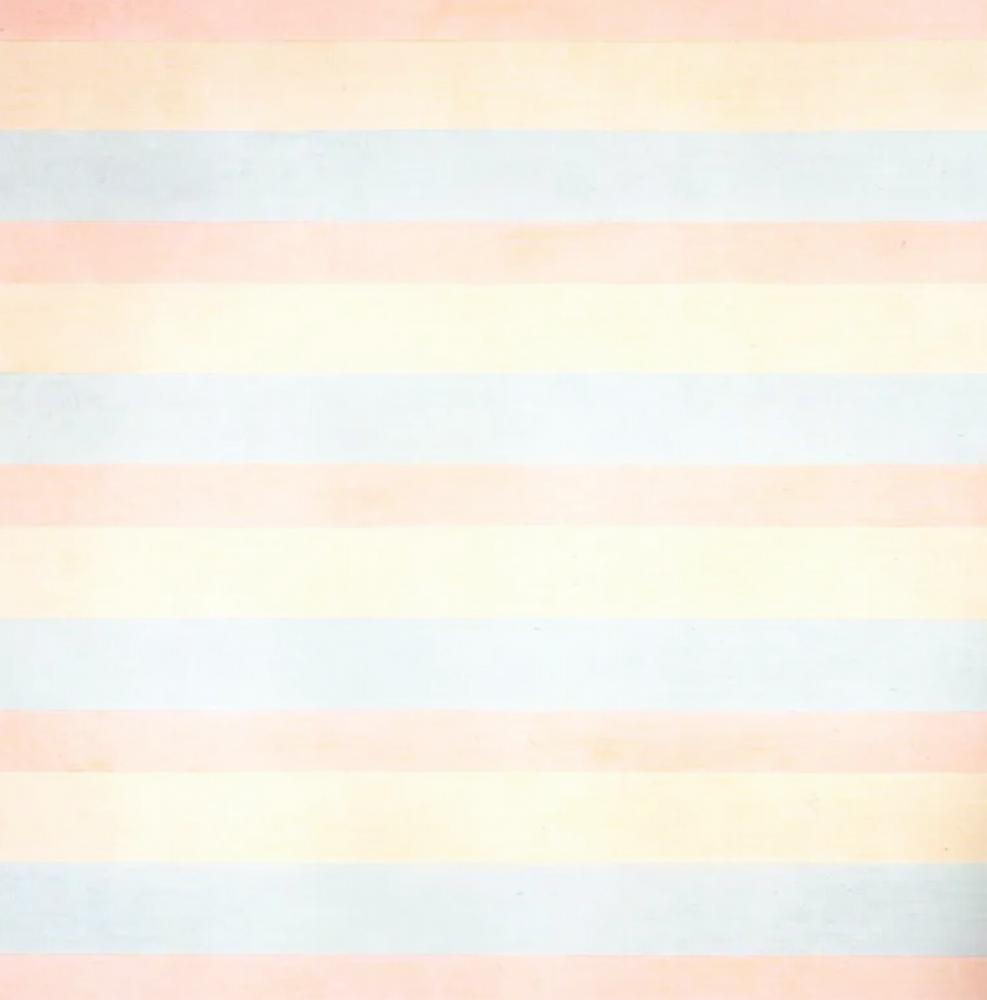

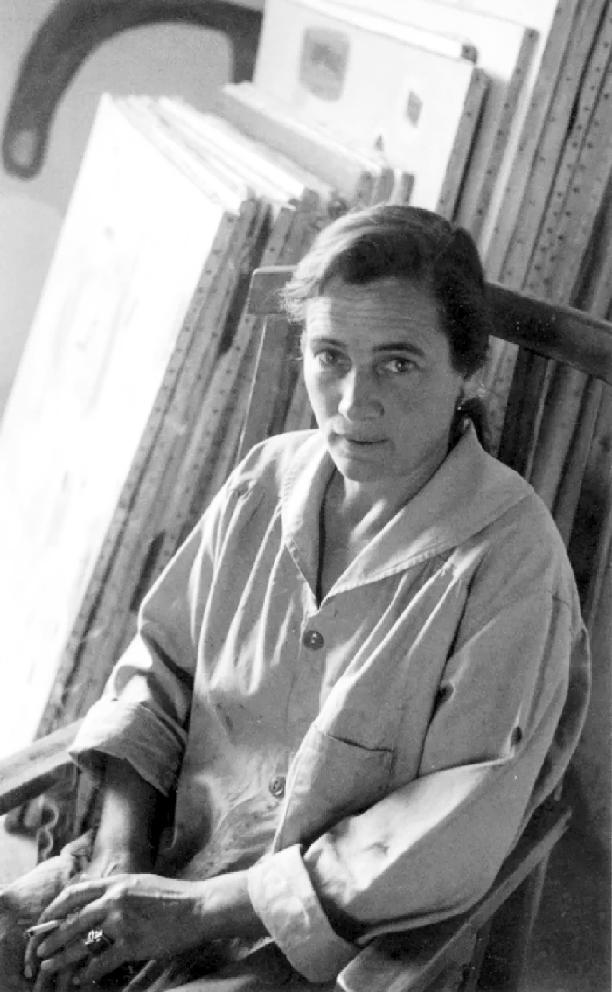

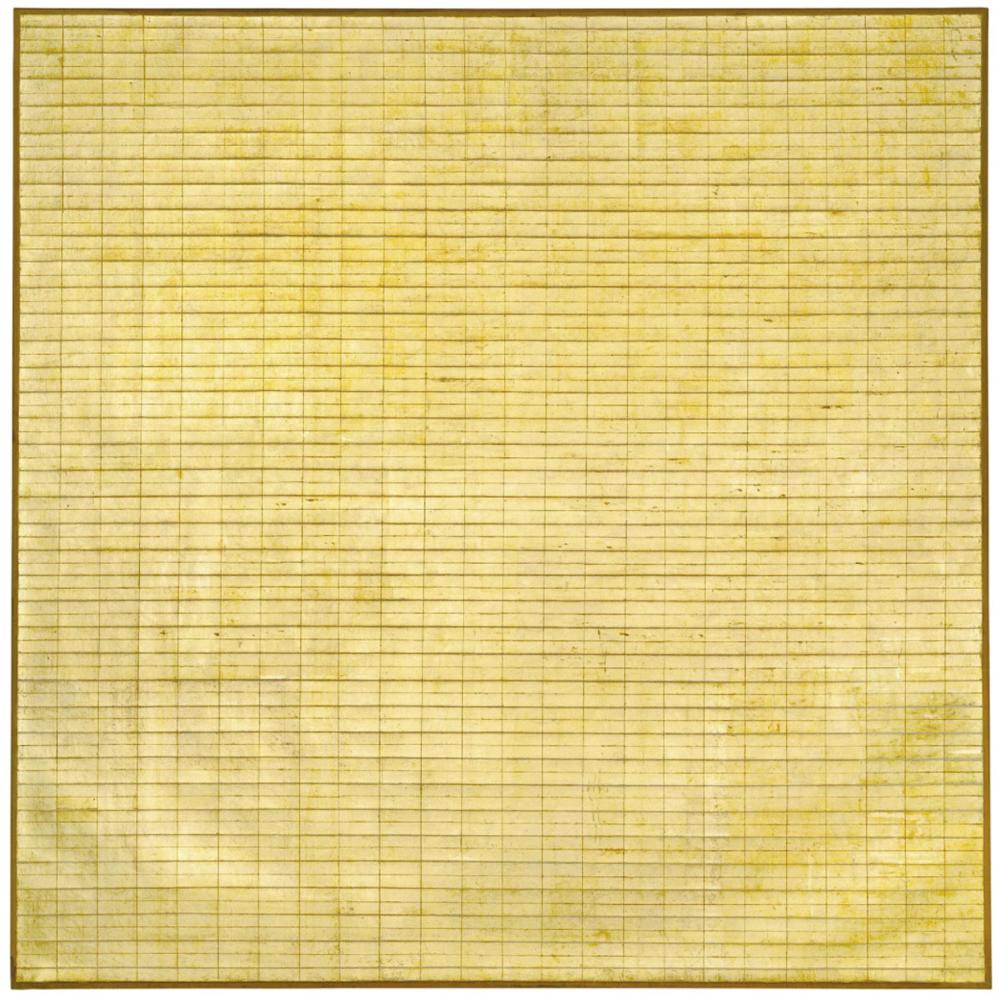

AGNES Bernice Martin was an American abstract painter born on March 22, 1912 in Macklin, Saskatchewan, Canada. Her work has been defined as an “essay in discretion on inward-ness and silence”. Although she is often considered or referred to as a minimalist, Martin considered herself an abstract expressionist.

She once said: “To be an artist, you look, you perceive, you recognise what is going through your mind. And it is not ideas. Everything you feel and everything you see and everything that your whole life goes through your mind, but you have to recognize it, go with it and really feel it.”

Martin said that she believes in always living in happiness and love, and never going for anything lesser.

Despite her largely solitary daily life, Martin shared her unique point of view in a number of interviews and lectures over the last four decades of her career. In them, she consistently advocated for an unburdened life and the pursuit of an experience of perfection and beauty that results only from a deep state of self-awareness.

Instead of thinking that social understanding will lead us to the truth, Martin believed otherwise. “It is understanding yourself. And to start on that, you have to look in your mind and see what you are thinking about. Because the truth is, you are unconscious of your own thoughts until you catch yourself.”

As an artist, Martin always advocated being intentional with every painting. “You can’t be in an unconscious state and paint. Because whatever is in your mind, and not the subject matter, but the feelings that you have related to that subject matter, is what you’re going to paint. So, the beginning is not actually painting. The beginning of painting is not you putting down green, and then thinking you like pink, so you put down pink. Painting’s not about that anymore than music is about this sound and that sound. It’s a whole thing. It’s something you can’t resist representing. It’s something that drives you to expression, and it’s irresistible.”

Martin left New York City abruptly in 1967, disappearing from the art world to live alone. After eighteen months on the road camping across both Canada and the western United States, Martin settled in Mesa Portales, a remote mesa outside of the small town of Cuba, New Mexico. In 1974 and 1976, Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield recorded two conversations with her there. In these excerpts, Martin discussed the concept of truth, the responsibilities of the artist, handling failure, and the importance of understanding one’s own mind.

“To be an artist, you look, you perceive, you recognise what is going through your mind. And it is not ideas. Everything you feel and everything you see and everything that your whole life goes through your mind, you know. But you have to recognise it and go with it.”

Towards the end of her life, Martin became happier and more social and moved into a retirement community in Taos, New Mexico in 1992. During that, she drove a spotless white BMW, one of the few extravagances in a life still dedicated to extreme material simplicity, to her studio each day.

For Martin, artists need to be aware of the inspiration that comes and go. “It changes our expression. The best thing about it is that it tells us the next thing to do. Without it, we feel lost. We think, oh, what shall I do and what shall I do, and why was I ever born and everything. But the thing is that not only in artwork but in life itself, we wait in readiness and with patience for the next step in awareness of truth. Of reality. The revelation of truth is the process of life. When you get distracted with this and that, and people say, look at this, and look at that, and you’re looking every way. And you’re spreading yourself out, and you allow people to distract your mind entirely, you will soon feel as though you’re terribly lost and frustrated.”

“Because you have left the process of the revelation of truth, or the seeking of truth, or whatever you want to call it. You have left the path of life. It isn’t the mysterious thing that people make it out to be, the path. You have to find out what your reaction to life is. When you find out about yourself and your reaction to life, then you will know the truth.”

In 1994, the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, part of the University of New Mexico, announced that it would renovate its Pueblo-revival building and dedicate one wing to Martin’s work. The gallery was designed according to the artist’s wishes to accommodate Martin’s gift of seven large untitled paintings made between 1993 and 1994.

“The artist has to have an absolute awareness of what he does. If you’re desperate and your inspiration is not coming through, then you probably will fall back on the illustration of an idea.”

“It all comes from attempting to illustrate from an idea instead of the experience coming right through. Now the way to have the experience come right through is that you simply have to be able to clear your mind so it can get through.”

Like so many mystics before her whose quest has been the pursuit of discovering the answer to the most fundamental question of all existence, Martin faced the all-pervasive fear inherent within the human psyche and transmuted it into a personal consciousness of being, a poetic passage of exquisite colour on the path to the threshold of the sublime.

“Anger, all the passions, they’re not real. They are what I call the exhaustibles. All the exhaustible things, like anger, you know how quickly it passes. Even the sense of seeing beauty is a very exhaustible thing, seeing it with your eye. If you see something that looks very, very beautiful, but if you kept your eye on that and looked and looked and looked, the beauty would disappear from it, because the eye is exhaustible. But then the inexhaustibles, they’re within the mind, you see. And the beauty that you see within the mind, it really never disappears. Now the inexhaustibles, they go on forever, that’s reality. They go on without change. But anything that is exhaustible is not real.”

Her final days in December 2004, were spent in the infirmary of the retirement home, surrounded by a few of her closest friends and family members.

“We start out with high hopes because people have taught us that just around the corner is happiness and contentment, and all you have to do is be good and try hard and all that. Well, you find out that you can be just as good as you possibly can be, and I mean, you try as hard as you possibly can try, and you still have, you know, the same old thing. You have failures and successes, no? Some things fail and others succeed.”

“Well, then you get quite desperate, you know. And you think, I’m going to work and work, and I’m not going to have any failures, right? But then you find out that failures are inevitable. That you cannot possibly, none of us, you can’t even draw a straight line. You know that. And you can’t have things, and you can’t have all days in which you are sunny and good-natured and everything like that. And you can’t be sweet to people. And you can’t please people either. Well, that is the development. The development is of oneself.”

Martin was adept at using language opaquely, creating a screen of words that could veil her from the gaze of the world. Like her enigmatic, resistant paintings, her statements are designed to express something beyond the reach of ordinary understanding, weapons in a campaign to devalue the material and elevate the abstract.

“I don’t know why it is that people have a tendency to doubt their own mind. To neglect your own mind, that’s like to neglect your consciousness. That’s like to give up all hope of joy and happiness.”

“You’re the only one that can discover for you the meaning of anything. What it means to you. By that, I don’t mean intellectual meaning. I mean, what it means, how it makes you feel. You have to see whether you really are happy or if you are sad. You have to investigate what goes through your mind.”

She wanted to be buried in the garden of the Harwood Museum in Taos, near a room of paintings she had donated, but New Mexico law forbade it, and so in the spring after her death, a group assembled at midnight and scaled the adobe walls with a ladder.

It was a full moon, and they dug a hole under the roots of an apricot tree, placing her ashes in a Japanese bowl lined with gold leaf before scattering them in the earth.