IN the previous article of this two-part series, I outlined the many negative health impacts of childhood obesity. For the second part, we will shift our attention to the opposite side of the spectrum- children who are underweight.

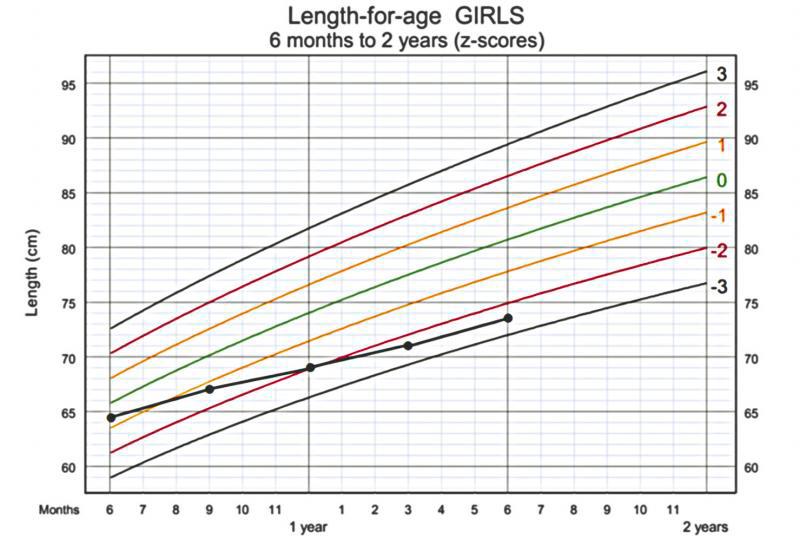

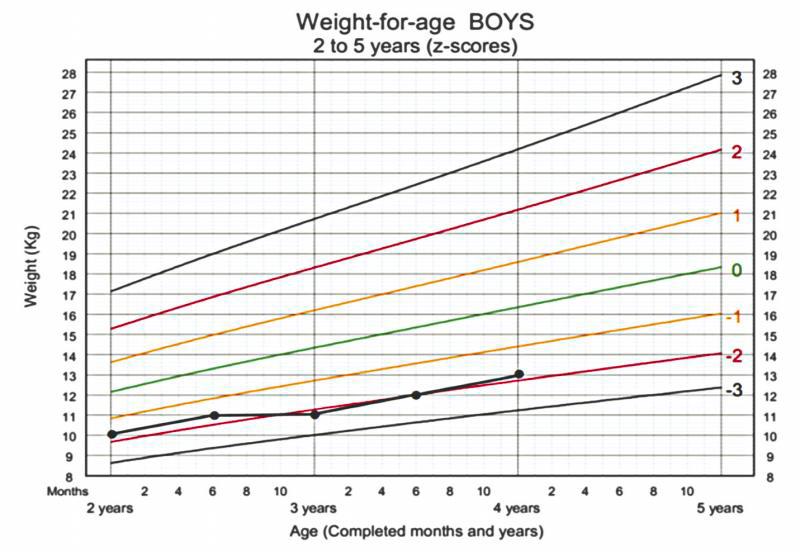

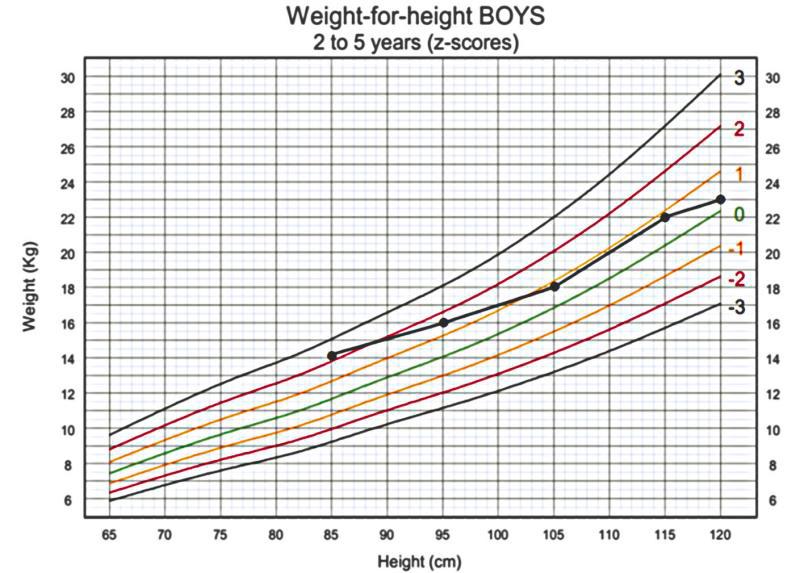

The term “faltering growth” is used to describe children who are not growing at the expected rate for children of similar age and gender. The World Health Organization (WHO) has standardised the definition of faltering growth as two standard deviations (z-score of -2 to -3) below the mean for age and gender.

While we know that Malaysia holds the title of the most obese nation in South East Asia, a Global Nutrition Report in 2018 also puts us as the worst in ASEAN in terms of nutrition. The criteria of interest were a certain percentage of the population with growth stunting, anaemia in women of reproductive age, and obesity. In ASEAN, Malaysia is the only country to be reported to fulfil all three “burdens” listed above.

Local statistics estimate that in 2018, approximately 20% of our Malaysian children, or about 500,000 children, have faltering growth.

It has long been established that poor growth is strongly associated with long term deficits in cognitive functioning and academic performance. The development of the child is delayed and the child is not able to achieve their expected learning potential in school. Often, the psychosocial problems that contribute to faltering growth including poverty and coming from a broken family play a part in further restricting the child’s abilities.

Paradoxically, in low-income populations, early growth stunting is also a risk for subsequent obesity owing to improper nutrition resulting in the double burden of undernutrition and then obesity. A possible explanation is that the troubled family may opt for a mainly carbohydrate-laden diet lacking in other necessary nutrients due to the high costs of living.

80% of cases of faltering growth are attributed to inadequate intake. This may be environmental (due to poverty), social (poor knowledge about proper diet, improper milk dilution, child neglect etc.), or related to feeding difficulties (medical conditions such as cerebral palsy, cleft palate etc.).

The remaining 20% are due to increased caloric demands (e.g. in children after major surgery or have chronic illnesses) and inefficient utilisation of calories (e.g. due to chronic diarrhoea/ vomiting, children with diabetes etc.). This list is non-exhaustive and there are in fact many possible medical causes of faltering growth.

In identifying faltering growth, early recognition is best. During the first 2 years of life, all children have scheduled visits to healthcare facilities for vaccinations, and it is during this time when routine measurements of weight, height, and head circumference are taken. More than just the absolute number of the measurements, the trend of the parameters have to also be taken into consideration. Beyond 2 years of age, it is recommended to have an annual visit to the clinic for growth measurement up until at least 5 years old.

Early recognition and early steps in managing faltering growth work wonders in allowing the child to grow healthily and achieve their maximum potential.

Dr Yeap is a paediatrician attached to KPJ Sentosa KL. Through his articles, he aims to help increase public awareness of the common issues associated with children’s health.