JUST like his previous works, there are many layers to Tash Aw’s latest book We are Survivors.

One moment, you think the book is about its Chinese-Malaysian protagonist who spent time in prison for killing a migrant worker, and the next, you realise that the story is also a reflection of our society and how its marginalised people, both locals and migrant workers, have much in common.

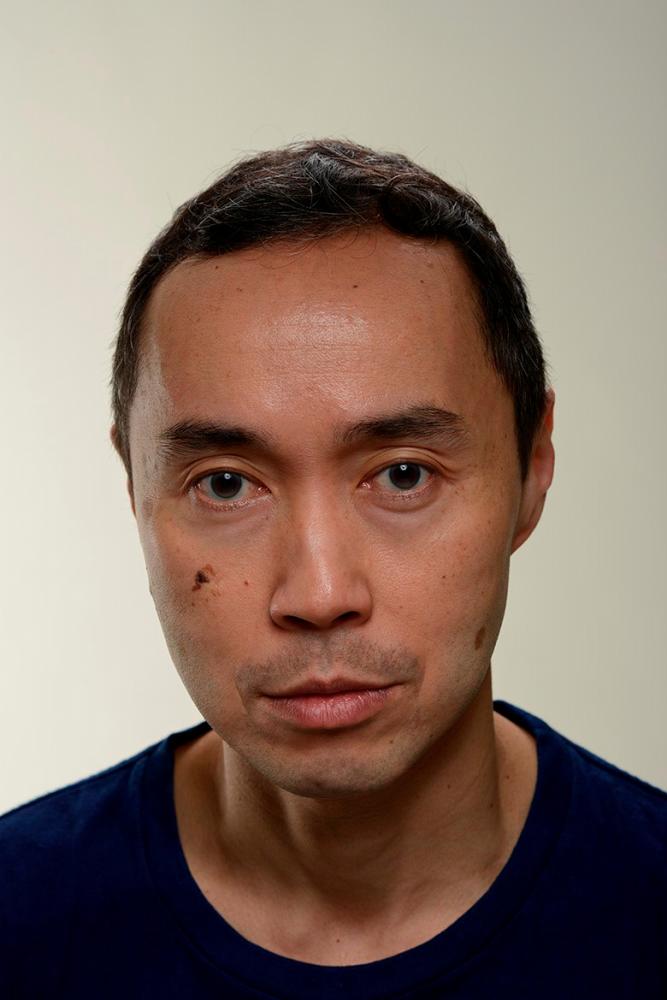

Aw, who was born in Taipei to Malaysian parents, became famous in the literary world after his 2005 book, The Harmony Silk Factory, was longlisted for the then Man Booker Prize.

He went on to win the Whitbread First Novel Award for the book.

He wrote two other acclaimed novels, the 2009 Map of the Invisible World and the 2013 Five Star Billionaire, as well as the 2016 non-fiction novel The Face: Strangers on a Pier that was a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize.

As we sat down and spoke about We are Survivors, Aw revealed that he has been based in Kuala Lumpur for the past two years.

We Are Survivors tells the story of Lee Hock Lye a.k.a. Ah Hock, who wants to move away from the tiny fishing village he grew up in.

Stuck doing poorly-paid menial labour, Ah Hock regrets being unable to provide a better life for his mother and his wife.

To earn some extra money, he agrees to help his friend Keong track down some runaway migrant workers – who turn out to be Rohingya – but Ah Hock ends up killing one of them.

The book veers back and forth between the past and present to give us a better understanding of what led Ah Hock to do the unthinkable.

There is a passage in We are Survivors where the first Bersih rally is discussed, and the pessimistic Ah Hock states that he does not see the point in being a part of the crowd.

Aw said that he had actually finished writing the book before the last general election in May 2018. “I have been following things and watching how they are all unraveling. It is very, very messy.

“That whole period after the election was incredibly optimistic, especially in Kuala Lumpur and Petaling Jaya.

“[These days] Malaysia is such a divided country in so many ways. It is hard to pick up the papers and hang on to that sense of optimism.

“We, who are of a certain financial and social background, have a different view of politics from other people who come from much poorer backgrounds.

“For them, whether it is Pakatan Harapan or Barisan Nasional, life is going to be really tough. They can’t see a correlation between a change in government with how they are going to survive until the end of the year, or even until the end of the month.

“It is very hard for some people to see how it would affect them, especially when they are on the lower side of the social spectrum.

“[And] if you are a migrant worker, it really has no meaning for you.”

Important issues such as the need for cheap labour, and why migrant workers are often hired instead of local workers, is discussed in the book.

“They are human commodities,” said Aw. “We are basically paying for what their bodies can fulfil. There is no acknowledgement of them as human beings.

“For me as an ethnic Chinese I find this very troubling, because for the vast majority of Chinese-Malaysians, our ancestors came to Malaysia under those kind of circumstances.

“More than other people, we should understand what it is like. I am really interested in how social conditioning reproduces itself.”

In the book, Ah Hock does reflect on how his grandparents arrived in Malaysia, and even mentions how his grandmother did not want to give out her real address to anyone.

Aw said: “The treatment that they received is so internalised that they reproduce it on to the migrant workers.

“It is one of those insidious things that if you don’t actually stop and think about it, it becomes a cycle that perpetuates itself.”

Describing how the idea to write this book started, Aw said he had previously written a short story on the interactions between Malaysians from lower social backgrounds and migrant workers.

Aw found that the lives of his middle class friends in Bangsar are so insulated that when food is brought to their table, there is no acknowledgment of the human being who is doing the task.

He points out that in some businesses, upper level management may never talk to the migrant worker who does the menial work but instead, rely on a Malaysian worker to talk to the migrant worker for them.

“Normally, in literature when you read about foreign workers, it is normally about rich people talking about their servants. It is a story that leads to nothing interesting.

“What is interesting is people who are actually in competition with migrant workers, how they figure out their relationship.”

Tash Aw’s We are Survivors is available at major bookstores nationwide.